we create strategic content for businesses doing good in the world.

November 19, 2025

6mins

Imagine walking along your favourite stretch of coastal sand — the bush turkeys scratching at the dunes, the salt in the air, the Pandanus trees (Pandanus tectorius) framing the path like old friends. Then you notice something’s wrong. Whole stands of those trees are dying, their crowns collapsed, their roots exposed to the wind.

That’s exactly what happened to coastal ecosystem specialist, Joel Fostin. In 2014, while studying near Agnes Water, a coastal town in the Gladstone Region, he realised the iconic Pandanus were disappearing.

“I was attending uni studying environmental science, focusing on fire ecology and the damaging effects of fire on ecosystems. One day, I was surfing in Agnes, my old home break, and all the Pandanus around were dead or dying. I climbed a tree and took photos… I remember seeing whole stands gone,” Joel recalls. “No shade, no habitat, no Pandanus — it changes the entire feeling of the coast.”

.png)

.jpg)

The cause was not age or drought, but an introduced Planthopper, Jamella australiae — also known as the Pandanus Planthopper — which in elevated levels, damages trees, and making them susceptible to lethal pathogens.

First identified on Queensland's Sunshine Coast in the early 1990s, the Pandanus Planthopper was later linked to Pandanus dieback in other regions as well. By the early 2000s, this dieback had spread to areas such as the Gold Coast and northern New South Wales. Despite the discovery, the issue grew.

And the more he looked, the worse it became. From the Gold Coast to Yeppoon, thousands of trees were falling, tens of thousands on K’gari (Fraser Island),taking with them the shade, the wildlife, and the coastal protection and character that defines Queensland. And in that moment, Joel made a promise to himself: if no one else were going to save them, he would.

.png)

To the average Australian or tourist, Pandanus trees are simply part of the scenery. But their presence is undeniably important to the survival of our coast. The role of the Pandanus tree in Australia runs deep — ecologically, culturally, and emotionally.

“The biodiversity supported by the Pandanus is impossible to overstate,” says Joel.

“At a time when global concern about insect decline is growing, this single tree species quietly provides habitat for 100s of invertebrate species — many of which are yet to be named, studied, or fully understood. And that figure doesn’t even account for the species we haven’t discovered yet (at least 15–20 host specific insect species), or the complex web of interactions that unfold within its leaves, roots, and crown. Its extraordinary level of host specificity offers a stark reminder: if one pandanus tree dies, an entire community of life may disappear with it,” he adds.

An example of this is the the Calliphara imperialis (pictured below), which was first collected in Queensland in 1770 and named in 1775. iIt was one of the earliest Australian insects to be documented. Remarkably, even after centuries, specialists had little knowledge of its lifecycle or host plants—until Joel discovered they spend half of each year on Pandanus plants.

When we consider this in the broader context — the number of other tree species declining along our coastline, each with its own hidden ecosystems — the scale of loss becomes confronting. Beyond its ecological importance, the Pandanus is one of the most iconic species on Australia’s east coast, woven deeply into tourism, education, and cultural identity. Protecting it means protecting far more than a single tree; it means safeguarding a whole living world.

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

Joel explains that their aerial roots grip dunes, preventing erosion and buffering storm surges along the coast. Their wide leaves cool the sand — crucial for maintaining the gender balance of endangered sea-turtle hatchlings, which depend on the sand's temperature to determine sex. The fruit, roots, and fibres have also sustained First Nations communities for millennia, being used for food, shelter, clothing, tools, and much more.

“They’re a keystone species,” Joel says. “When Pandanus disappear, so does a whole chain of life — insects, spiders, geckos, frogs, native rats, snakes. It’s not just a tree; it’s a home, a pantry, and a climate regulator all in one. Everyone is concerned about rising sea levels. Pandanus are at the forefront of the beach, with an immense root system that can reach up to 30 metres. They can grow in any soil type, so their ability to prevent erosion is important.”

For Joel, the Pandanus dieback wasn’t just scientific — it’s personal. He grew up surfing under their shade, the smell of salt and sap a familiar comfort. “They’re part of my childhood,” he says. “When you start to see them dying, it’s like watching memories fade from the landscape - I couldn’t let that happen.”

.jpg)

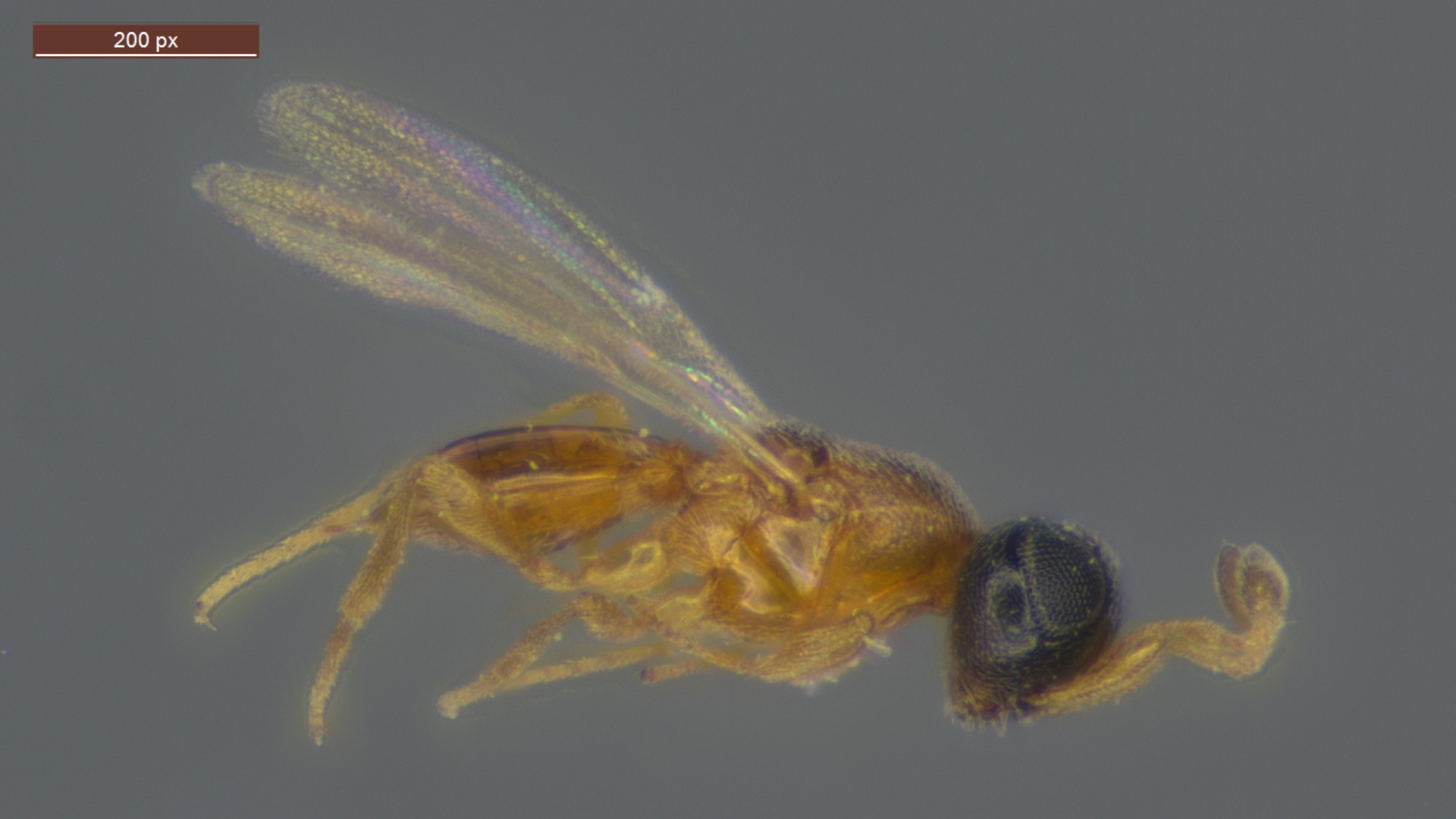

In 2015, Joel discovered the importance of a natural ally in the battle against Pandanus dieback: a microscopic parasitoid wasp from the genus Aphanomerus, specifically identified as Aphanomerus nr. pusillus.

Joel discovered that the wasps’ larvae preyed on developing planthoppers, effectively curbing their population and preventing further dieback. And it proved highly successful. In 2015, Joel dedicated several months educating and assisting rangers from Queensland Parks and Wildlife Services and the Fraser Island Defenders’ Organisation. Together, they strategically deployed the wasps across 37 affected sites on K’gari (Fraser Island), where more than 30,000 Pandanus had perished. The results were remarkable. The intervention swiftly brought planthopper numbers down to normal levels, allowing arborists to remove the mould-affected leaves and preventing further tree mortality. Within a year, healthy new crowns appeared. The ecosystem began to breathe again.

“It’s a perfect example of how nature already has the answers — we just need to support it.”

The idea was simple, and the results were highly promising: if these wasps could be bred and released along the coast, with six-monthly monitoring and wasp translocations, they could naturally restore balance to affected Pandanus stands. But as political priorities shifted and funding waned, many of the early breeding programs faded, leaving entire regions without ongoing management.

While official programs stalled, Joel refused to let the work end there. With no funding and little guidance, he began experimenting in his own home — turning a spare room into a makeshift breeding lab. Through months of trial and error, he learned how to raise the wasps until they were strong enough to survive release. Armed with jars of his home-bred wasps, he started taking them to the dunes, climbing the Pandanus himself — sometimes with the help of friends — and “wasp-dropping” (sometimes with drones) the insects onto infected trees one site at a time.

With no initial funding and little institutional backing, Joel spent years often operating as a volunteer scientist, driving the coast loaded with wasp containers, monitoring infestations, and teaching QPWS and Indigenous rangers, Council staff, and community groups how to manage dieback. His dedication earned recognition, including a Volunteer of the Year commendation from Healthy Land and Water, and partnerships with coastal councils from the Gold Coast to Livingstone Shire.

Today, his “Pandanus Dieback Education and Information Page” serves as a public hub for sharing research, practical tools, and community updates on this ongoing battle for the coast.

Joel’s mission now extends far beyond a single species. He’s advocating for integrated coastal management — long-term funding, community-led programs, and a shared responsibility for the ecosystems that protect us. After seeing how quickly one spark can undo years of recovery, he’s also pushing for better fire education and planning across coastal regions.

“Fire, pests, erosion — they’re all connected,” he says. “Healthy coastal ecosystems are our first line of defence against sea level rise. We need to treat them that way.”

Looking ahead, Joel continues to establish a coast-wide Pandanus recovery network linking local councils, Indigenous ranger groups, and research organisations. His goal is to ensure that what began as a one-man mission becomes a sustainable, collaborative effort — one that continues to protect Queensland’s living coastline for generations to come.

.png)

Queensland’s coastline spans more than 7,000 kilometres, encompassing mangroves, wetlands, rainforests, and the World Heritage-listed K’gari — the largest sand island on Earth. Pandanus trees, with their iconic screw-leaf crowns and prop roots, anchor many of these fragile systems. Their survival ensures the stability of dunes, the safety of turtle nesting sites, habitat for an immense level of biodiversity, and the visual identity of coastal towns from the Sunshine Coast to Cape York. Conservation programs like Joel's demonstrate how science, traditional knowledge, and community stewardship can converge to restore balance — one tree, one wasp, and one volunteer at a time.

Discover More:

- Healthy Land and Water – Coastal Programs

- University of the Sunshine Coast – Pandanus Dieback Research

- Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service – K’gari Conservation

Every Pandanus saved represents more than a tree — it’s a story of balance, resilience, and care for Country. Joel Fostin’s work shows how local action can drive real ecological change, one coastline at a time. You can help protect Queensland’s coastlines by learning to recognise Pandanus dieback, supporting restoration programs in your area, and planting native species in your own backyard.

To learn more or get involved, visit the Pandanus Dieback Education and Information Page and discover how you can be part of this coastal revival — because when we care for the coast, the coast cares for us.

You have successfully joined our subscriber list.

REGIONAL STORIES acknowledges the Traditional Custodians of country throughout Australia and their connections to land, sea and community. We pay our respect to their Elders past and present and extend that respect to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples today.

We share the real, raw, and remarkable stories of regional Australia — stories that inspire change, spark connection, and give regional voices a national stage.